Today, I read this post of r/eli5 which asks whether time is a real tangible thing or just a concept invented by humans. And if it is a real, tangible thing – how can that be proven? And this got me thinking, because time is really weird in a lot of ways – and most people have no idea about it.

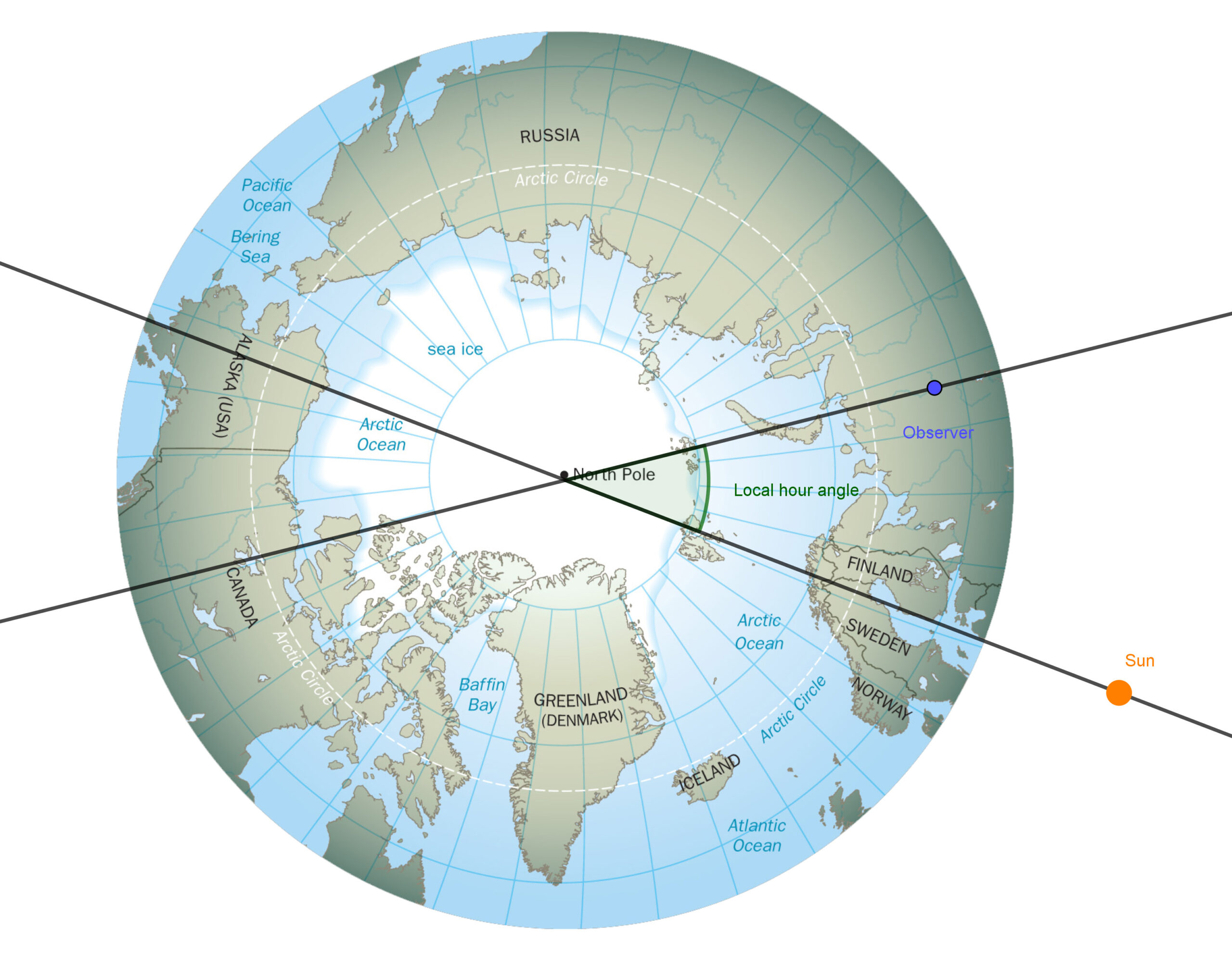

Firstly, think about what time really is in your opinion. For most people, it’s the thing that is displayed by a watch or clock. But how is it defined? And where is time actually coming from? I had to take an astronomy lecture in my studies, and when you get started with astronomy, you learn about lots of weird things, the first weird thing being that time is actually an angle. Yes, time is the angle between your local meridian and the meridian that is currently pointing towards the sun.

But there’s one flaw with this definition: Using this natural definition of time, the length of one day can easily be defined by observing when the sun is exactly vertical over your current location – which we call solar noon. The length of one day would then be the time between two consecutive solar noons – with the flaw being that this definition has seasonal effects – so one day in December would be longer than one day in September (source).

So, what did humanity do as a consequence? Since it is very inconvenient to run your clocks slower in the winter, we defined a timescale that runs at the average speed of this solar time definition – such that the solar noon happens every day on average around 12 o’clock.

Fun fact: The reason that time is actually just an angle is also the reason why WGS84-coordinates can be written in degrees – minutes – seconds format like so: N 52° 17′ 42.907” E 10° 27′ 29.171”

Once you wrapped your head around this weird fact that time is actually just an angle, the next thing comes around: Sidereal time. Because actually, the earth does not take 24 hours to make a full rotation – it takes 23 h 56 min 4.0905 s or 23.9344696 h (source). But why does everyone say that it takes 24 hours? Because as we know, the earth does not only rotate around its axis, it also revolves around the sun in an elliptical orbit – creating seasons and a time unit we call a sidereal year. So, in those 23.9344696 hours the earth has not only rotated around itself, it has also revolved a teeny tiny bit around the sun – around 2600000 km per day to name the number (source) and this causes us to see the sun under a slightly different angle relative to all the other stars around us (around 1° per solar day). For that reason, it only makes sense for astronomers to define everything around this weird sidereal time – which runs at almost the same speed as solar time, just a tiny bit slower.

And if all of this hasn’t confused you enough, let’s talk about leap seconds. Yeah, that’s right: Leap years are not confusing enough – let’s introduce leap seconds. Because the earth does not rotate at a constant rate (since it’s not a perfect ellipsoid and there are other disturbing things, like a moon), the time that is measured by atomic clocks (the international atomic time) slowly moves away from solar time (i.e. what we humans perceive as time). So, from time to time, a leap second is introduced. And what does that mean practically speaking? When the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS) decides that a leap second is due, clocks will go from 23:59:58 to 23:59:59 then 23:59:60 and only then roll over to 0:00:00. But to make matters worse, not all timescales implement leap seconds. UTC (the time most of us use) does, but some timescales like GPS time (the timescale used by the GPS system) or the aforementioned international atomic time don’t.

If all the aforementioned things have not freaked you out yet, I have more things to come: Because so far, we only looked at time from an astronomical point of view. We have yet to look at it from a physical point of view. So, let’s introduce special relativity: The faster a body travels, the slower it perceives time (so-called time dilation). This obviously has little effect when we move by foot, by bike or in cars because we travel too slowly compared to the speed of light, but if you send an atomic clock on a satellite (like GPS satellites have) and send it on an orbit where it’s travelling with approx. 14000 km/h, you have to account for the fact that that damn clock installed on the satellite is simply running slower.

And last but not least, even human definitions of time have changed over the years: Not only did we have different calendar systems (like the Gregorian and Julian calendar), but different countries used different calendar systems – meaning that the time and even the date were different depending on what side of a border you lived. And believe it or not – this is still true today! Different countries are in different time zones, and if you believe to be part of a country for political reasons, you also accept their time definition. The most current example of that is indeed Ukraine: The pro Russian groups use Moscow time and the Ukrainian government uses eastern european standard time – which is one hour ahead of Moscow (source). And even if you don’t want to dive into political conflicts, there’s this weird oddity called the international date line, where the clocks on both sides show the same time, but one is exactly one day ahead of the other. This has lots of disadvantages for trading and the economy, hence countries tend to switch from one side of the international date line to the other depending on whom they are mostly trading with.

To summarize then, time – the simple concept of a clock ticking at a rate of one second per second – is actually very convoluted: Not only does it depend on physics and astronomy, it also depends on how we measure and how we define time – and consequently on geographical, political and sometimes even religious aspects.

Now, you might ask how all of this affects your daily life. If you’re an astronomer or physicist, well, you knew what you were getting into. Hence, my sympathy is limited. But if you’re a programmer: My sincere condolences. You were probably lulled in by the simplicity of Unix time and didn’t know that you just opened pandora’s box when you started working on timing things. In that case, your go-to solution should be to just use a library – much like Tom Scott suggested in his video. And if you’re just a regular girl or guy, simply appreciate what craziness has gone into making your wristwatch tick at a rate of one second per second.